From February 23rd to June 9th, 2019 the exhibition of the Venetian view-painter (vedutista).

Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto (1697 - 1768), is today the most famous Venetian

artist of the eighteenth century, the vedutista or view-painter who more than any other

codified the appearance of Venice in the form that still pertains in the global collective

imagination. And not by chance: his views exalt it as a city of water and celebrate its

spectacular appearance, making it, if possible, even more grandiose and wondrous. In his

works, Canaletto does not present a simple succession of monuments but leads us

through a real visual experience thanks to an extraordinary technical ability,

‘enlightened’ in his scientific definition of the images, and it is the city itself that becomes

a work of art in its own right.

In that same century, Venice was swept by a number of complex and surprising

contradictions: it was one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world, lived in and

visited by cultured merchants and refined collectors and foreign travellers; the Republic

of Venice was still the most important state in the Italian peninsula, but at the same time

the first signs of the decadence that foreshadowed its fall (in 1797) were already visible.

Trades and manufacturing were languishing and artists sought and obtained more

remunerative commissions elsewhere, although the patrician families had impressive

wealth to rival that of European rulers. It was in this context that the last great period of

Italian art developed in Venice, one that achieved international fame and excellence in

every artistic genre: the veduta, but also in portraiture, landscape, sculpture, the

decorative arts and great history painting.

For this exhibition at the Palazzo Ducale, it was decided to relate Canaletto’s works to

those of the other masters of the Venetian school, and his individual development with

the facts that marked the history of art in the lagoon throughout the century of which he

was a protagonist. The horizon is thus expanded in chronological, temporal, and genre

terms, combining great painting with drawing, engraving, the decorative arts and

porcelain. With the exhibition of Canaletto at the Palazzo Ducale, what we see is the

story of a master standing out among the great of Venetian art, characterised by the

comparison between the two dialectical poles of imagination and observation, which are

here not antithetical but mutually attractive, between the fantasy of the city’s decorators

and the attention to reality of the vedutisti.

The veduta – literally view – was born in the early years of the century, with the

publication in 1703 of a collection of over 100 engravings entitled “Le fabbriche e vedute

di Venezia disegnate, poste in prospettiva et intagliate da Luca Carlevarijs”; Carlevarijs

was the artist with whom Canaletto later competed and swept aside in the search for

patrons. In this first decade Venice saw the blossoming of a creative season of great

vitality, which included the youthful Canaletto and his contemporary Giambattista

Tiepolo.

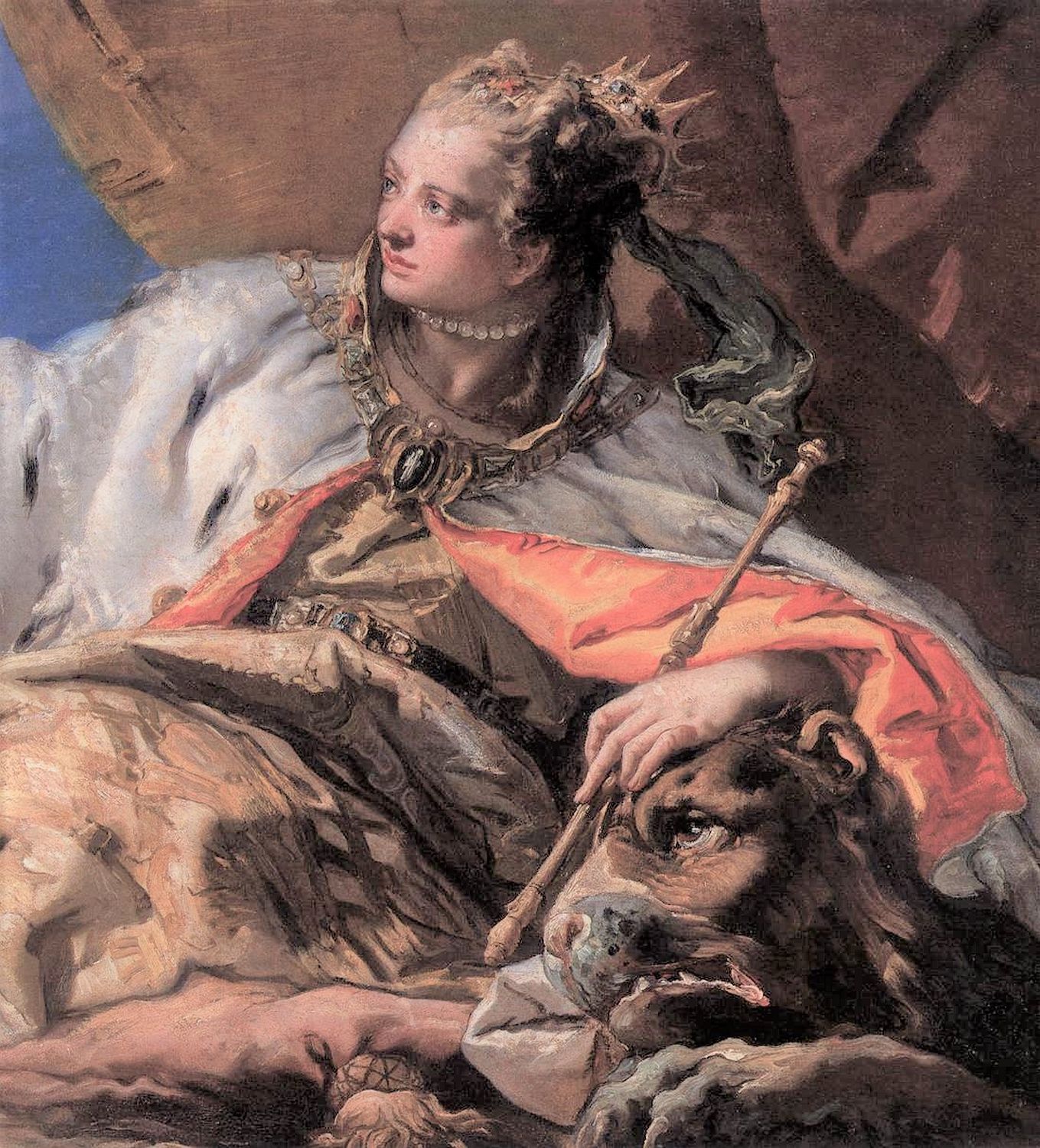

Tiepolo himself is the author of the canvas that welcomes the visitor in the first room

and which depicts Neptune offering the gifts of the sea to the allegory of Venice. Outside

the Ridotto by Francesco Guardi contrasts the mythological image of the city dominating

the seas with the vision of the foreign traveller, more interested and responsive to a

depiction of a festival and carnival city. As a synthesis of the two visions, in the centre of

the room visitors see the model of the Bucintoro, the Doges’ galley used for celebrations;

a vessel that floats but does not sail, gilt all over and the perfect symbol of a Venice that

lavishly and unnecessarily celebrates itself.

Here the art of Canaletto begins. In his twenties, Canaletto followed his father, a painter

of theatre sets, to Rome and subsequently returned to Venice to devote himself to

painting alone, producing masterpieces that have always characterised the image of

Venice and the history of the depiction of great views. In 1737, Francesco Algarotti

published Newtonianismo per le Dame, a popularising volume about Newton’s theories

on light set out in a series of dialogues about light and colour. The light Canaletto started

to paint became cooler, crystal clear and gives an effective optical truth to the paintings

and to the subjects, constituting a sharply-focused encyclopaedia of the types of

activities in the lagoon city.

Canaletto soon exceeded Carlevarijs and Sebastiano Ricci in fame and skill, flanked by a

group of artists who were innovating the language of history painting, portraiture,

interiors and social occasions. Whether working in the large European cities, like his

contemporary, Tiepolo, at royal courts, where Rosalba Carriera was drawing pastel

portraits that were overturning the celebratory canons of portraiture, or in the lagoon,

like the embroiderer and painter Giulia Lana, much appreciated by Giambattista

Piazzetta.

Pietro Longhi is an exquisitely Venetian phenomenon. In 1741 he inaugurated

a new type of painting for the city, genre painting, which portrays Venetian patrician

figures in their daily occupations. Similar attention to the more domestic and less

imperial aspects can be found in a certain form of vedutismo, even in Canaletto, such as

in the extraordinary The Stonemason’s Yard, an exceptional loan from the National

Gallery in London, in which we see the building of a Venetian palazzo on the bend of the

Grand Canal where the wooden Accademia bridge would stand in the future. The point of

view is itself unusual in the depictions of Venice.

The exhibition in the Palazzo Ducale presents 25 works by Canaletto, with some pictures

never before displayed in Venice and loans of great value from prestigious private

English collections. Around these, a fascinating layout in 11 rooms includes a further 80

paintings and 20 sculptures, as well as a large presence of prints and drawings and an

extraordinary display of porcelain, for a total of over 270 items. Porcelain was a secret of

China for a long time, but in the eighteenth century it began to be reproduced in Europe,

and in that century it constituted a perfect expression of the rococo spirit with its airy,

light lines, that were impossible to attain using other materials. The third largest

manufactory in Europe was in Venice: Vezzi, which had to close a few years after its

opening. Only a few and very rare pieces survive and are displayed here in a room next to another presenting a formidable collection of Meissen porcelain.

As the century drew to a close, the splendour of the Serenissima faded with it, while

Francesco Guardi composed views corroded by light very different to the sunny

geometric certainties of Canaletto, and Tiepolo, home from Spain, began painting his

serial work of Pulcinella figures. In Venice the Accademia was finally born, in line with

Rome and the rest of Europe, and in the art scene Antonio Canova began to come to the